More than 150 years after it was drawn up by the Bordeaux Brokers Union, the 1855 Bordeaux classification’s influence shows no sign of diminishing.

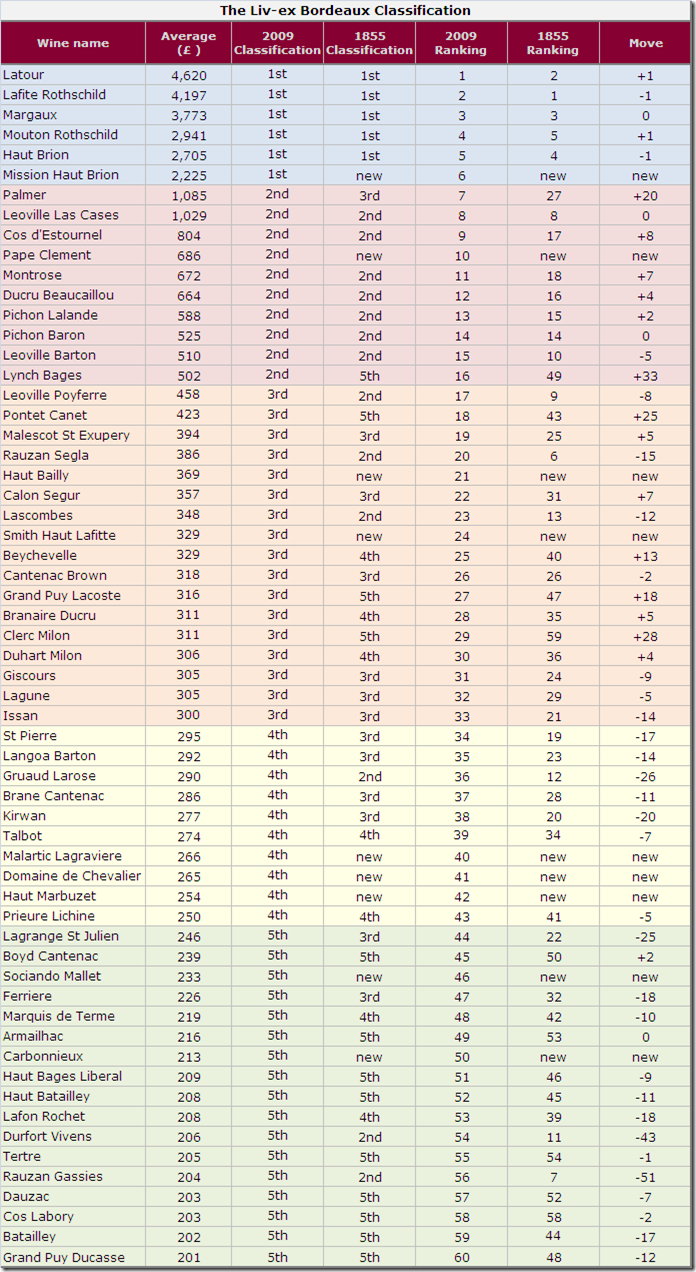

With the next en primeur campaign fast approaching, we thought it would be interesting to recreate it. To base it wholly on price – as the 1855 classification was – and include only the major estates of the Left Bank. In essence, to create the classification that would have been drawn up if today’s prices were those prevalent 154 years ago.

The 1855 Classification was produced by the Brokers at the request of the Bordeaux Chamber of Commerce. Its purpose was to be used as part of the regional display at the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1855. The Brokers returned their classification just two weeks after the original request was made. As Dewey Markham Jr writes in his excellent study, ‘1855: A History of the Bordeaux Classification’: “There were no chateau visits, no requests for samples, no tastings involved in the establishment of the rankings, nor was there any need for them.”

The 1855 drew on the many existing classifications of Bordeaux wines that were prevalent at the time, most of which had five distinct ‘crus’. It was not intended to be a definitive selection; it was intended as just another in the long line of such classifications, with others sure to follow.

The letter from the Brokers to the Chamber, which accompanied the return of the classification, made this clear: “You know as we do, Sirs, how much this classification is a delicate thing and likely to arouse sensitivities; also it was not our thought to draw up an official state of our great wines, but only to submit for your consideration a work whose elements have been drawn from the best sources.”

They also mentioned the price each cru was worth in the market, with each having a defined price band. To qualify for the Liv-ex Bordeaux Classification wines had to be from the Left Bank (including Pessac-Leognan) and be produced in quantities of more than 2,000 cases. Only the first wine of each estate was considered. We then calculated a price for each estate’s wine, by taking an average from the last five vintages (2003-2007) for a 12x75cl case, stored in bond (excluding duty and sales tax).

We then took £200 as the minimum average case price to be included in the classification, which left us with 60 wines, just one less than in 1855.

As the brokers did in 1855 we split up the wine according to price band, which are as follows:

1st Growths: £2,000 a case and above

2nd Growths: £500 to £2,000

3rd Growths: £300 to £500

4th Growths: £250 to £300

5th Growths: £200 to £250.

It remains a matter of academic debate whether the chateaux were listed in their respective 1855 classifications in order of price/quality – although the evidence seems to point to them being so. We have assumed they were for the purposes of this analysis.

Download Liv-ex Bordeaux Classification

The most striking aspect of the Liv-ex Bordeaux Classification is that there are six first growths, with Mission Haut Brion joining their exulted ranks. From the data, it seems clear that it belongs in this company. The difference in price between Mission and the wine below it (Palmer) is larger in percentage terms than that between any other adjacent wines in the classification, with the former twice the price of the latter.

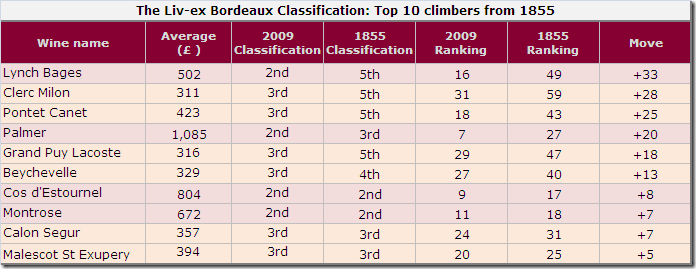

As you can see from the top climbers table, despite the rigidity of the 1855 classification, a number of chateaux have managed to dramatically increase the price they receive for their wines vis-à-vis their peers. The biggest climber is Lynch Bages, up 33 places, with the rest of the list reading like a ‘Who’s Who?’ of Bordeaux’s most progressive and ambitious estates— with Palmer, Pontet Canet, Clerc Milon and Cos d’Estournel all featuring.

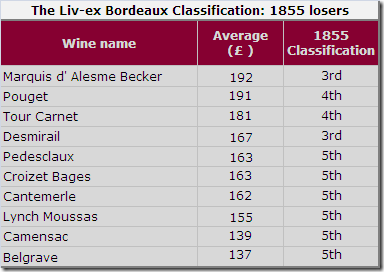

Obviously, where you have winners, you also have losers, although it would fair to say that is the exceptionally high standards now prevalent in Bordeaux that have caused their exclusion , rather than any specific failings on their part.

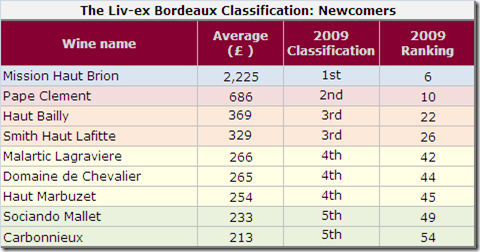

The newcomers are generally from two groups: the top wines from Pessac-Leognan that were overlooked in 1855 – such as Mission Haut Brion, Pape Clement and Smith Haut Lafitte – and the top Cru Bourgeois of the Medoc – such as Sociando Mallet and Haut Marbuzet.

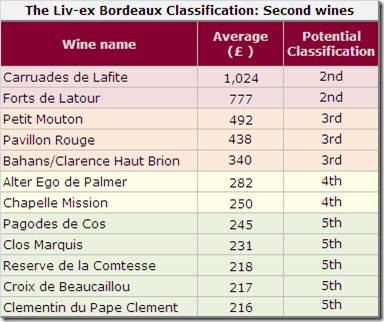

The second wines of the great chateaux are a complicating factor. They obviously didn’t exist in 1855, so we decided to classify each property on the basis of their first wine. It is interesting to note, however, that if they were included as separate chateaux, 12 would make the cut, with Carruades de Lafite and Forts de Latour reaching the level of second growths.